The Android Developer's Journey into Hardware Observability

In this article, I walk through how the growth of internal observability tooling for an AOSP device might look like, and the variety of pitfalls one might encounter as they scale from 1s to 10s to 1000s of Android devices in the field, based off my experience talking to AOSP developers and teams, and personally as an Android app developer working on AOSP hardware.

Table of Contents

Introduction to Android hardware observability

With the popularity of mobile app development over the last decade, many developers are at least vague familiar with what’s involved with shipping and maintaining an Android app. But if your only experience is with Android apps and you are suddenly thrown into a project developing on Android hardware, it can be surprising how the single mobile app is just a tiny fraction of the complexity involved.

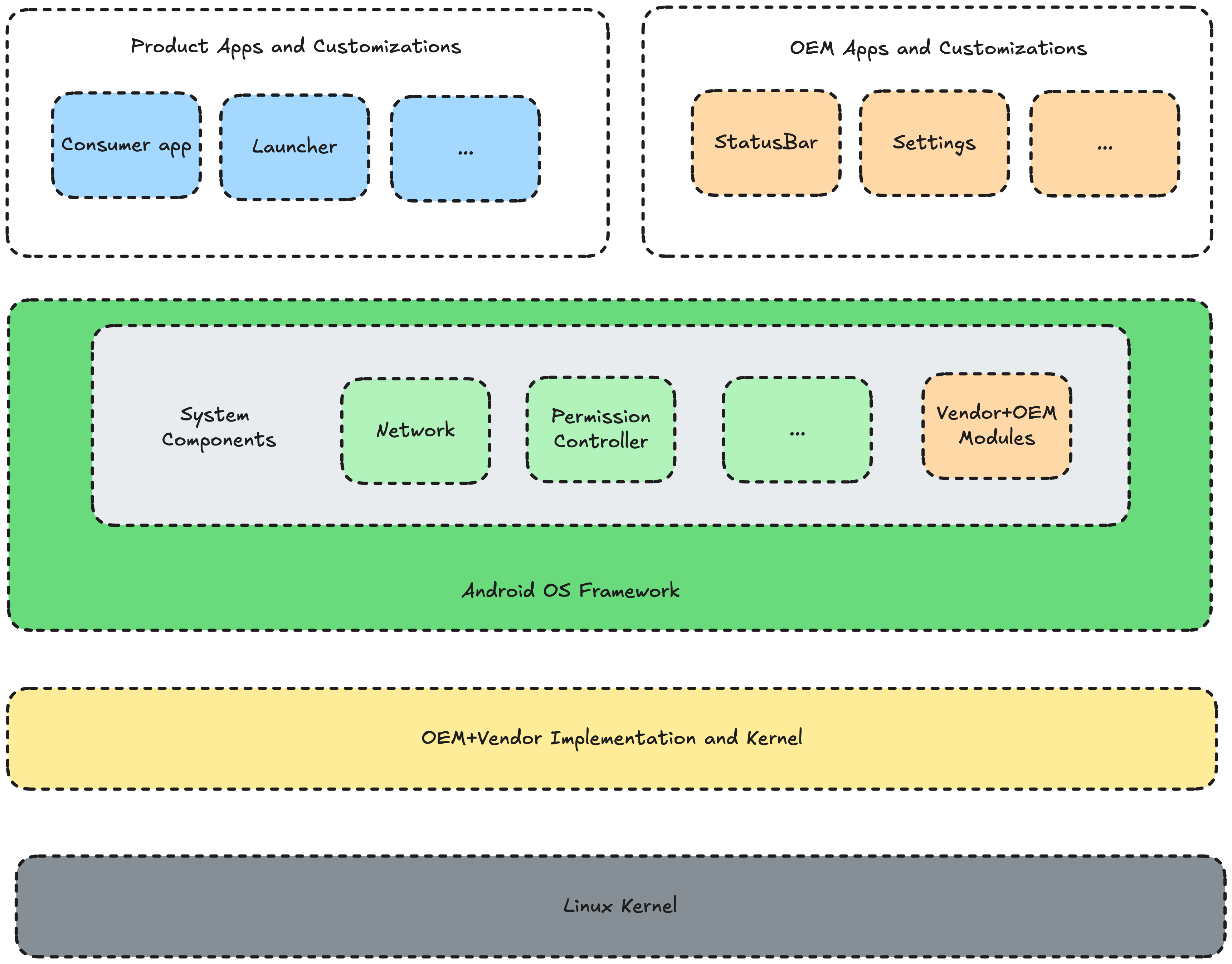

When you ship an Android app to Google’s Play Store so users can install it on Android smartphones from Google, Samsung, Motorola, or some other manufacturer, you’re only responsible for delivering a single Android app. But when you deliver Android hardware, there are tens (hundreds?) of Android apps on the device to think about — like Status Bar, Settings, Software Updater, Dialer, Messaging, Documents, Keyboard, and more. And there are even more native services that run as part of the core Android OS. Each custom Android device is also usually ordered from an ODM (Original Design Manufacturer), which customizes the base version of the Android Open Source Project (AOSP) with ODM-specific changes to support that specific SoC (system-on-a-chip) by providing drivers for hardware components. So at the end of the day, at the bare minimum, you’re responsible for a device that’s running parts of your own Android apps, parts of your ODM’s customizations, and the whole of AOSP, which is also running a customized version of Linux.

To make things even more complicated, if your team ordered the Android hardware from an ODM, you might not contractually have access to the source code of the OS (since the ODM would rather not let you see the types and quality of changes to AOSP), which significantly limits your ability to dig into and understand the operation of the device, instead relying on the terms of support in your contract.

This web of complexity might not seem like a big issue, but it is the nature of all software and hardware today that there are bugs, and the more complicated the system, the more complicated the bugs that can arise. It’s unrealistic to expect to catch all bugs during development, so what we need is a variety of tools to help diagnose and fix problems when the hardware is in the field and in our customer’s hands.

Evolution of observability

If you’re developing Android hardware, it’s likely the core of your device is several standard Android mobile apps, and you can start by using the mature ecosystem of Android app observability tools like Crashlytics, Bugsnag, Instabug, or others, to maintain the quality of those apps.

User error reports

The first hiccup in development often arises when a user encounters a bug not captured by existing app observability tools. User error reports can be quite vague (e.g., “the screen just went black!”), making it essential to gather more information from the affected device. Early in the process of Android development, many developers come across Android bug reports, which often leads to establishing a process for users to generate and share these reports. In some cases, the app can guide users through creating a bug report and then emailing it to the engineering team.

There are many obvious problems with this approach: they might already be unhappy with the experience and unwilling to cooperate; they might have returned the product already; they might be busy and miss the message. But if there is a low number of devices in the field, this can feel somewhat sustainable with only minimal engineering effort.

Automatic error reports

Of course, as there are more users, we can improve the process here by spending more engineering time to reduce the time the customer spends. We can first focus on automating the bug report collection to avoid having the customer do the work — when they call in with an issue, we can remotely trigger a bugreport for them and then write code to asynchronously upload the report in the background. To trigger the upload, we can develop a new native service in our AOSP build to listen for a push notification. This might be a big feature in itself if push notifications are not supported.

Then, we’ll have to find a sustainable, secure location to upload the bugreports to. To start, we could compromise: the bugreports can be sent to a personal email in the interim, the bugreports might never expire, or the bugreports might be uploaded into an existing system that wasn’t meant to handle that file size or volume. But it should work, and once we can download the bugreport, it often has enough information for us to find the bug.

Capturing device logs

After automatic error upload, we likely encounter situations where the

bugreports might not be enough. So we get the idea to upload the device logs as

well. We’ll quickly discover the different types of

logcat buffers on the device: like

main, system, or crash, and see that some kernel errors showed up in the

system buffer in the past. The size of the buffers are quite small, so you might

have to find ways to increase the size of the buffers to persist them for

longer. And it could make sense to append these device logs onto the same

bugreport system as before.

Reactive improvements

Over time, this process could improve iteratively, as it’s generally good enough, and we end up being tasked to work on other projects until there’s a fire requiring us to capture more information we don’t have. If there isn’t enough data in the bugreport, or in the device logs, there might be more areas of AOSP to query and add to be uploaded, like tombstone files, dumpsys, or recovery logs, or the many system services. We may eventually refine the backend too, so there’s a dedicated area for viewing all the uploaded data by a single device or by user.

Common decisions to overcome

There are many decisions to make at each step of the observability journey that can either lead the developer astray technically or work well for a reasonable amount of time, but fail to scale as the number of devices observed increases. Each decision can result in a large amount of engineering time designing, building out, and testing the changes, but also maintaining the system over time as it gets more complex.

Push vs pull

While a push notification may trigger the collection of a report, the system as a whole is still pull-based, because they still require someone to request the data from the device. A symptom of this is that sometimes, when a bug happens, the affected user might take several days to reach out to customer support, and by that time, the data is not in the buffer anymore. Or in another case, there might be a delay in customer support that causes the data to be lost. Pull-based systems also make it awkward to pro-actively check how often an issue is happening across every device, because it means randomly choosing a number of devices to pull data from, on the off-chance it experienced the issue.

Converting an existing pull-based push system to automatically push data when it detects an issue can be difficult: the push system took some work and now needs to be spun down, the backend might not be designed for uploading a higher volume of data, the device will need to manage its cache of data and dedupe any uploaded information, and more.

When we initially discussed pulling error reports at a previous company, our AOSP device didn’t have push notifications (since it didn’t use Google Mobile Services), so we spent loads of time investigating and then re-building push notifications on Android using MQTT, and re-purposing an existing frontend to allow customer support to send a push trigger for the error report. But there were so many times where the error report just didn’t contain any information from around the time of the incident because it was requested too late.

Data analysis fatigue

Inevitably, after tens or hundreds of bugs and customers investigated and fixed or abandoned, the developer can get tired of manually combing through logs, and realize they can develop tools to parse the error report automatically. There’s often a lot of noise, and it generally feels possible to filter out what’s important.

Building this tool can feel initially good, but slowly, over time, the complexity of the data grinds progress to a halt. Sharing the tool within the company or as an open-source project can keep the momentum going, but unless there is a dedicated team involved with maintaining it, maintaining the tool can feel like a chore.

The tool itself is probably not perfect. While programmers can easily think about text analysis, a visualization is sometimes more effective, and while some time can be spent building tools like Battery Historian, it takes a ton of dedicated engineering effort to really design something that works over time.

At a previous company, it turned out that each of several Android teams had engineers who each built their own data parsing tool that looked through error reports and logs for information specific to that team. But as time went on and the teams changed ownership or the developers moved around, these tools became more and more unwieldy to use and eventually dropped as a relic of the past.

Campfire or Wildfire

After a certain number of devices, it becomes impractical to fix every bug on the device. Instead, teams start introducing a system of prioritization to determine whether a fire is a small campfire or a widespread wild fire.

If the team has a way to trigger data upload automatically, parse that data into something actionable automatically, uniquely identify one issue from another, count the number of times that issue occurs on how many devices, and persist this information in a queryable format somewhere, then they might be in a position where they can pro-actively understand what are the most pressing issues to fix. But it takes a ton of work to develop and maintain all the systems involved in that pipeline!

In my experience from the device developer side, a lot of progress can be made on the device-side so that the error reports can be uploaded to the right place. But when the data operations move from CRUD (create, read, update, delete) to actual data processing, the amount of cross-functional buy-in and expertise involved is an order of magnitude more difficult for a company to commit to.

Building a team with the right expertise

The reality is that all the work in designing, building, and then maintaining these systems, will require a team of engineers with diverse skillsets across the entire stack: AOSP developers are needed to collect and upload the data from the device and provide domain expertise, backend developers are required in order to maintain and scale pipelines as more and different information is processed, frontend engineers might be required to create a nicer way to download the data, data scientists will need to be involved to ingest the metrics and help set up charts, alerting, and design how to store and query the data efficiently. Staffing a full team just to maintain a hodgepodge observability solution is a tall ask, especially for many AOSP engineers who would rather be solving customer pain points.

Conclusion

There’s a ton of content on what observability means for Android apps, but content and tooling for AOSP device observability is sparse in comparison, leading many AOSP developers to build their own internal tools. And most AOSP developers end on a similar journey: they discover the limits of their apps observability tools, then they figure out they want to pull Android bugreports and logcat device logs, then they find a way to push the logs from the device instead of pull, and then they discover even more Android data they want to include, but would rather parse the data automatically, and do it for every device, not just the one they’re working on, and then they fight to build a team that could do all of this sustainably.

One of the reasons I joined Memfault was to build the tooling I wish we had previously because I ran through all the same roadblocks I described above, and helping other developers to learn the same lessons I had, in less time. And there are still many more lessons in AOSP observability to learn, so if you have experience with observability at scale, I’d love to hear from you.

See anything you'd like to change? Submit a pull request or open an issue on our GitHub