Monitoring a Low-Power Wireless Network Based on Smart Mesh IP

Monitoring IoT applications is essential due to their operation in dynamic and challenging environments, which makes them susceptible to various operational and connectivity issues. Application Performance Monitoring (APM) is the key to identifying and resolving these issues in real time, ensuring uninterrupted data flow and functionality. Moreover, the insights gained from APM can optimize device performance, ensure reliability, and reduce operational costs. Observability goes beyond APM and is a commonly addressed and well-understood topic for more advanced IoT device classes. When speaking of advanced device classes, we mean full-fledged micro-computers, e.g., a Raspberry Pi.

However, in the diverse array of IoT networks, cheap, ultra-low-power wireless systems have garnered particular attention, too. These systems commonly rely on battery-powered devices with resource-constrained MCU architectures such as the 32-bit ARM Cortex family. These systems are required to be reliable as well! Wireless Sensor Networks (WSN) are an example of such low-power wireless systems and are widely deployed in industrial environments to ensure a flawless operation of all the entities in a factory.

Because of the computational and power constraints inherent in these devices, it’s common for vendors to neglect APM capabilities. In my opinion, this is inconsistent with the fact that reliability is the most important feature from a customer’s point of view.

This blog post provides a practical tutorial demonstrating a simple APM solution for low-power devices. The solution leverages Zephyr RTOS on an nRF52, and SmartMesh IP on an Analog LTC5800 which can accommodate an arbitrary number of wireless motes. The motes can send a set of performance metrics at certain heartbeat intervals via a framework provided by Memfault. The framework is scalable and allows the creation of a customized group of metrics.

👉 A full white paper1 was written on this topic – take a look if you are interested in diving into the details!

Table of Contents

Technical Background

Before diving into APM in low-power wireless systems, let’s provide a brief history lesson of standards widely used in this type of network. Besides Wi-Fi (IEEE 802.11) or Bluetooth (IEEE 802.15.1), another standard dominates the IIoT world, namely LR-WPAN, or simply IEEE 802.15.4. In general, it is not as power-hungry as Wi-Fi and the mesh topology of IEEE 802.15.4 allows it to cover much larger areas than other low-power solutions such as BLE.

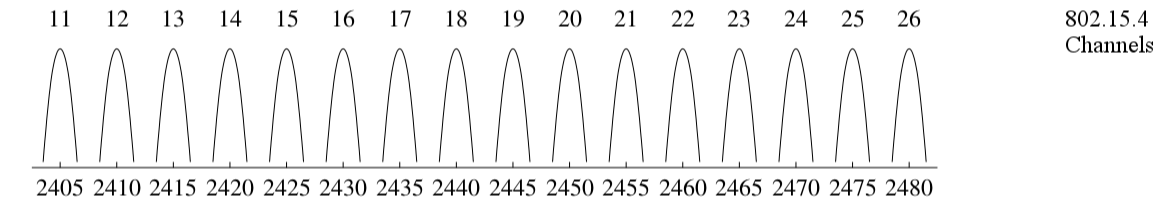

In 2012, Time Slotted Channel Hopping (TSCH) was first proposed as an enhancement of IEEE 802.15.4 (known as IEEE 802.15.4e), and in 2015, it was included in the related standard specification. TSCH deals with external interference and multi-path fading at the MAC layer. When two neighbor nodes exchange frames, they send subsequent frames at different frequencies, resulting in channel hopping. Therefore, the 2.4 GHz band is cut into 16 channels 2:

The idea is that if external interference or multi-path fading causes the transmission of a frame to fail, the retransmission happens at a different frequency and therefore has a higher chance of succeeding than if retransmitted on the same frequency. Therefore, TSCH makes the standard more robust and suited for industrial environments.

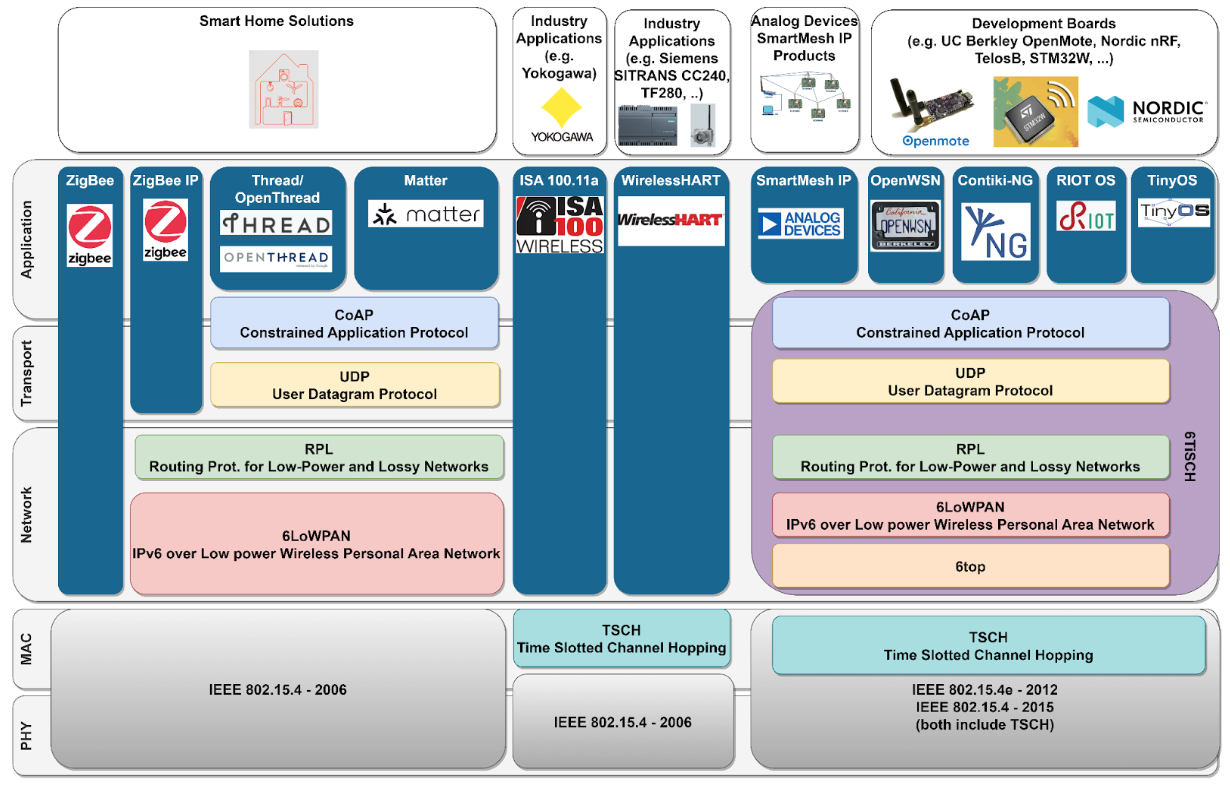

As IEEE 802.15.4 defines the characteristics of the PHY and MAC layer in the OSI model, several standards are building up on IEEE 802.15.4 in the upper layers. Zigbee, Thread, and Matter are popular examples that target smart-home applications mainly. Industrial solutions mostly rely on WirelessHART and ISA-100.11a which both employ TSCH. Besides the mentioned technologies, the IETF has put effort into defining protocols for integrating constrained devices, such as sensors, into the Internet. These protocols include 6LoWPAN, RPL, and CoAP. The IETF 6TiSCH WG was founded to create a standard that enables using them on top of the IEEE 802.15.4-2015 TSCH link layer. The resulting 6TiSCH stack is fully implemented in at least four open-source projects: OpenWSN, Contiki(-NG), RIOT OS, and TinyOS.

Analog Devices’ SmartMesh IP product line also implements a pre-6TiSCH protocol stack. This is a closed-source protocol, but the formulation stems from 6TiSCH 3. The technical overview of SmartMesh IP 4 and the results of industrial 6TiSCH performance evaluations 5 indicate that this standard may fulfill our ambitious requirements in terms of reliability. Since we consider reliability to be the major KPI of our system, the 6TiSCH architecture is demonstrated as the underlying model in this blog post.

Hardware Setup

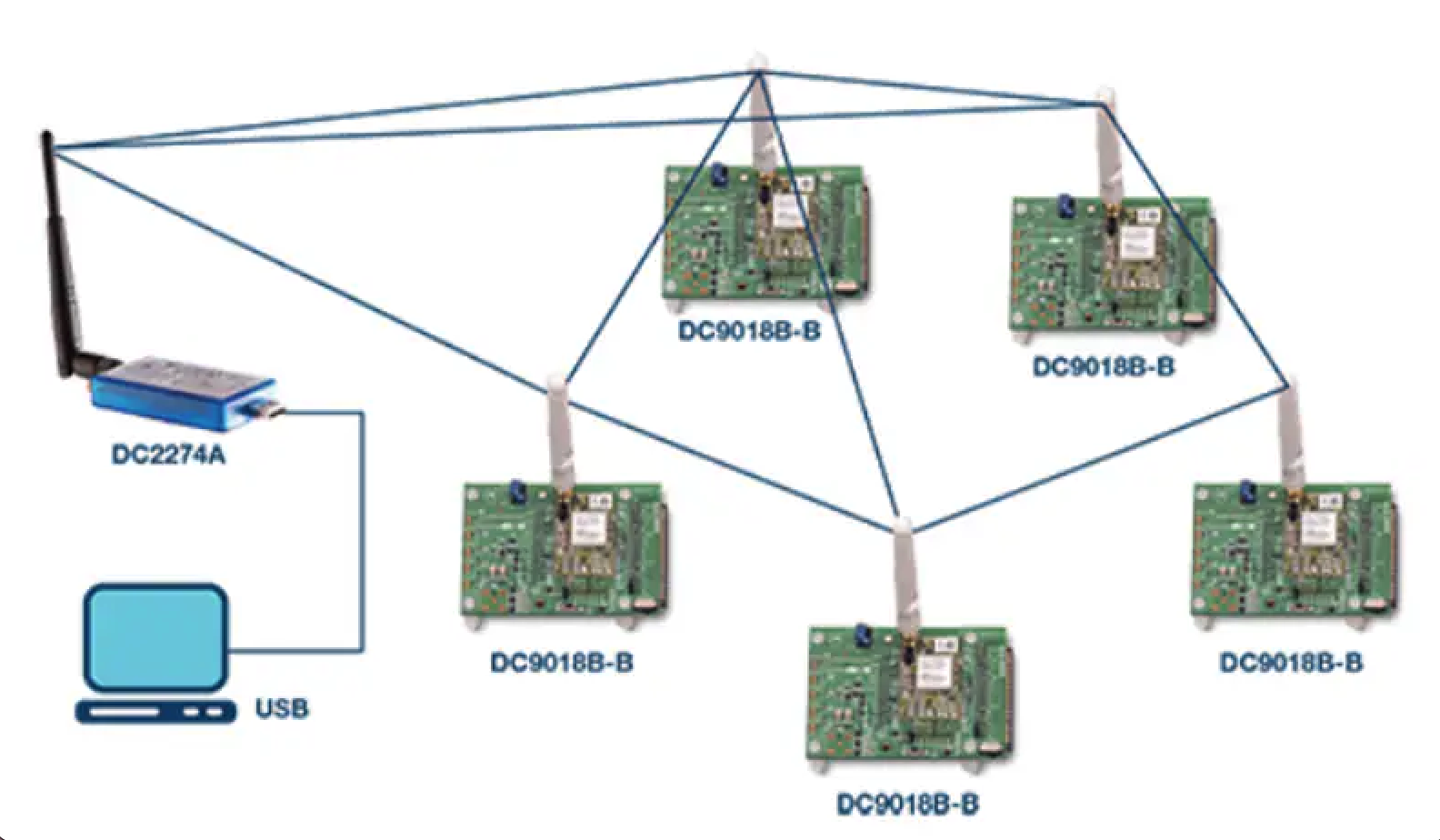

We use a HW setup that comprises a SmartMesh IP manager connected to a computer with internet connection, and a number of motes forming a wireless network based on a mesh topology 6:

The motes consist of a networking chip (LTC5800) and an application chip. Although the choice of the application chip is up to the user, we show two different setups based on Nordic’s nRF52 chips. While the nRF52s have a basic radio functionality, we do not use it and count on the networking capabilities of the LTC5800. Using the Nordic nRF Connect SDK (NCS) offers easy programmability of the application chip via the “nrfjprog” CLI and natively supports the use of Zephyr. The two setups shown in the following are almost technically identical, but they vary in terms of programming/debugging process, battery voltage supply, and size.

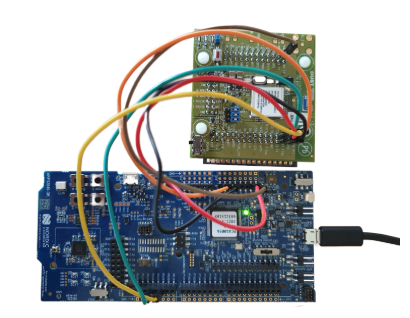

Option 1: nRF52840DK + DC9003A-B

The motes in Option 1 consist of an nRF52840-DK and a SmartMesh IP mote (DC9003A-B). They are connected via jumper wires to establish the UART connection and provide a power supply for the LTC5800 if desired. In general, both boards run on coin cell batteries.

The advantage of this solution is that the nRF52840-DK comes with an on-board SEGGER J-Link debug chip, which allows it to be programmed via USB. The SmartMesh IP mote needs to be set into “slave’’ mode. Switching between master and slave mode is possible by connecting the SmartMesh IP mote to the Eterna Interface Card (DC9006A). This operation only needs to be done once. Obviously, this hardware setup is large, fragile, and cumbersome.

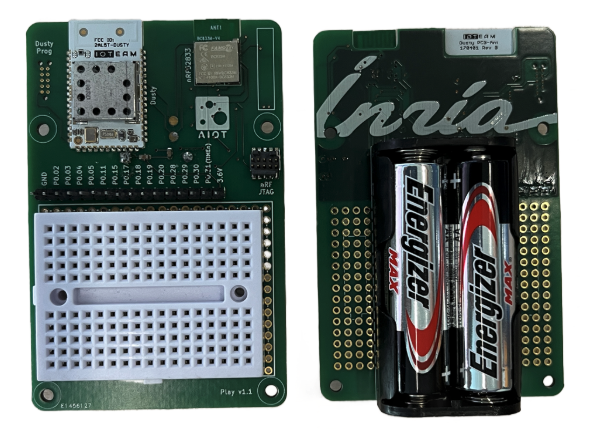

Option 2: AIOT Play

The Inria-AIO team has therefore designed the “AIOT Play” board 7. The two core elements are still the LTC5800 as the networking chip and an nRF52 as the application chip. The major difference to the first setup is that both chips and their connections are already soldered on a standard PCB. In contrast to the nRF52840DK from the first setup, the AIOT comes with a BC833M module containing an nRF52833. Another difference between the setups is that the AIOT relies on 2x AA batteries as its voltage supply. Additionally, an nRF JTAG connector is part of the board. It allows to programming the BC833M module via an external J-Link debugger or even via another nRF DK with an on-board debug chip. The AIOT Play is designed to easily set up and deploy custom applications by using the prototyping area, which contains a breadboard, allowing you to build circuits without needing to solder.

Integration of Memfault

In this section, we highlight the necessary steps to integrate Memfault as a monitoring framework into the application chip of our described setup.

One major distinction to make between how Memfault was intended to be used and how we are going to showcase it here is the data collection interval. Memfault is designed to collect pre-aggregated system metrics from devices every hour. In this post, we’ll gather metrics every few seconds to evaluate the performance of Memfault’s data serialization techniques, which leverage CBOR and advanced symbol file processing to optimize data transmission.

Memfault can be included in the nRF Connect SDK and Zephyr by editing the

west.yml file. When creating a new project in the Memfault cloud, the

generated project key must be pasted in the prj.conf file behind the

corresponding identifier CONFIG_MEMFAULT_NCS_PROJECT_KEY when using the NCS.

In the next step, we need to configure the metrics collection process. The NCS offers a small set of metrics out of the box, collected in a default heartbeat interval length of 1 hour. Obviously, we want to add a few custom metrics and adjust the interval length. Therefore, a config directory in the root folder can be created.

It may contain a memfault_platform_config.h file for setting a heartbeat

interval length by using the define MEMFAULT_METRICS_HEARTBEAT_INTERVAL_SECS.

Additionally, in a memfault_metrics_heartbeat_config.def file, we can define

custom metrics via the command MEMFAULT_METRICS_KEY_DEFINE(), which takes the

metric name and its corresponding type as arguments. After that, we can place

the corresponding Memfault heartbeat functions for metric collection, i.e., for

counters, timers or gauges, at the appropriate places of the application source

code. The metrics intended to be collected at the end of the heartbeat interval

must be sampled in the memfault_metrics_heartbeat_collect_data() function,

invoked when the heartbeat interval timer expires.

The data packetizer is the Memfault module that handles the transformation of

the collected metrics into a Memfault chunk, which is then given to the send

function. A function template showing the usage of the data packetizer is

available in the Memfault documentation. The function is called

send_memfault_data_multi_part(). In the beginning, the function checks to see

if there is data available. This is the case when metrics are ready to be sent

due to the elapsed timer of the heartbeat interval. Thus, the function can be

theoretically called at any time since new data is available when a heartbeat

interval is over. Therefore, it is recommended to call the function immediately

after the end of an interval. If metrics are available, a data buffer is

created. The buffer and the length of the chunk are passed into the send

function, i.e., ntw_transmit() from the SmartMesh IP C-library, handling the

UART communication between the application and networking chip. Then the packet

arrives via UART at the networking chip, where it is ultimately sent out via the

chip’s radio into the network.

The network manager is connected to an edge device with an Internet connection

at the network edge. In our setup, the network edge consists of the SmartMesh IP

manager which is connected via USB to a computer. From this point on, several

options are possible to ensure a reliable transfer of the Memfault chunks into

the Memfault cloud. In this tutorial, we decided to run the JsonServer.py

application from the SmartMesh SDK 8.

JsonServer.py connects to the SmartMesh IP Manager serial API and converts the

incoming notifications into JSON-based HTTP messages. Then, in

a separate script,

we take the HTTP messages and simply push the payload via the Memfault CLI to

the cloud.

The Memfault chunks finally arrive in the Memfault cloud. To process the data,

Memfault requires that the symbol file matching the compiled FW file, e.g.,

zephyr.elf, be uploaded to the service. It matches the incoming data to the

symbol file using a build ID. With this symbol file, Memfault extracts the names

of the metrics from it and combines them with the metadata and values of the

received Memfault chunk to write the metrics into a database and visualize them.

Since Memfault keeps all historical symbol files, it can process generated data

from current and past firmware versions.

Performance Analysis

Finally, we analyze the Memfault Chunk structure and show the current consumption associated with different heartbeat interval lengths.

Structure of Memfault Chunk

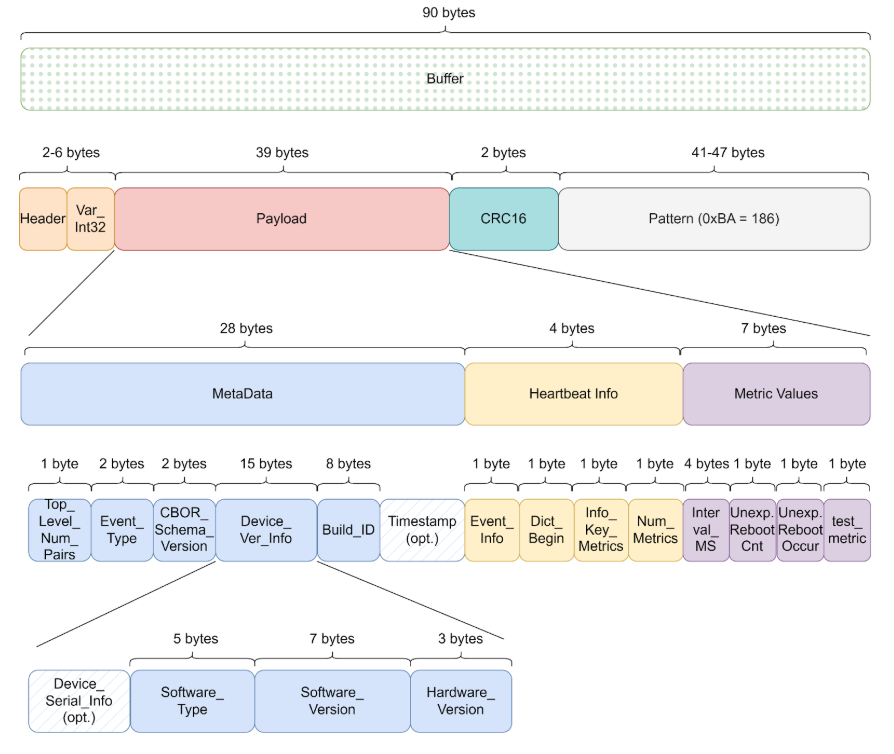

The buffer passed to the data packetizer should have a size that fits into the payload element of the network frame to avoid fragmentation. IEEE 802.15.4 frames have a length of 127 bytes. However, due to the header and multiple control fields, the size is significantly smaller and depends on the used protocol architecture. In our setup based on SmartMesh IP, a payload of up to 90 B is supported.

The buffer is handed to the packetizer, which grabs the available metrics and enriches them with additional metadata and heartbeat information. Additionally, a header is appended before the payload, and a CRC of the payload is computed and appended. The rest of the provided buffer is filled with a certain pattern. We analyzed the complete structure of a Memfault chunk in various debug sessions.

We tried to keep the Memfault chunk as minimalistic as possible to determine the

minimum size a single chunk can have. It turns out that there are several

metrics that Memfault and the NCS report by default. For testing purposes, we

disable them by setting CONFIG_MEMFAULT_METRICS_DEFAULT_SET_ENABLE=n and

CONFIG_MEMFAULT_NCS_STACK_METRICS=n in Zephyr’s proj.conf file.

Furthermore, we define a test metric, a simple gauge metric incremented by a periodic timer. We end up with a metrics section consisting of just four metrics in 7 B. In total, the Memfault chunk then has a payload size of 43 B, from which 39 B is the actual payload.

Besides the metrics, Metadata and Heartbeat Information fill the payload block.

These values have a fixed size, but we can specify the Device Version Info

fields, where we choose aiot as CONFIG_MEMFAULT_NCS_FW_TYPE. Since this

information is transmitted with every metric payload, choosing short device

version information is desirable in scenarios where every byte counts. In the

following step, the packetizer serializes the Memfault chunk using CBOR and

finally writes the chunk into the buffer.

Current Consumption Measurements

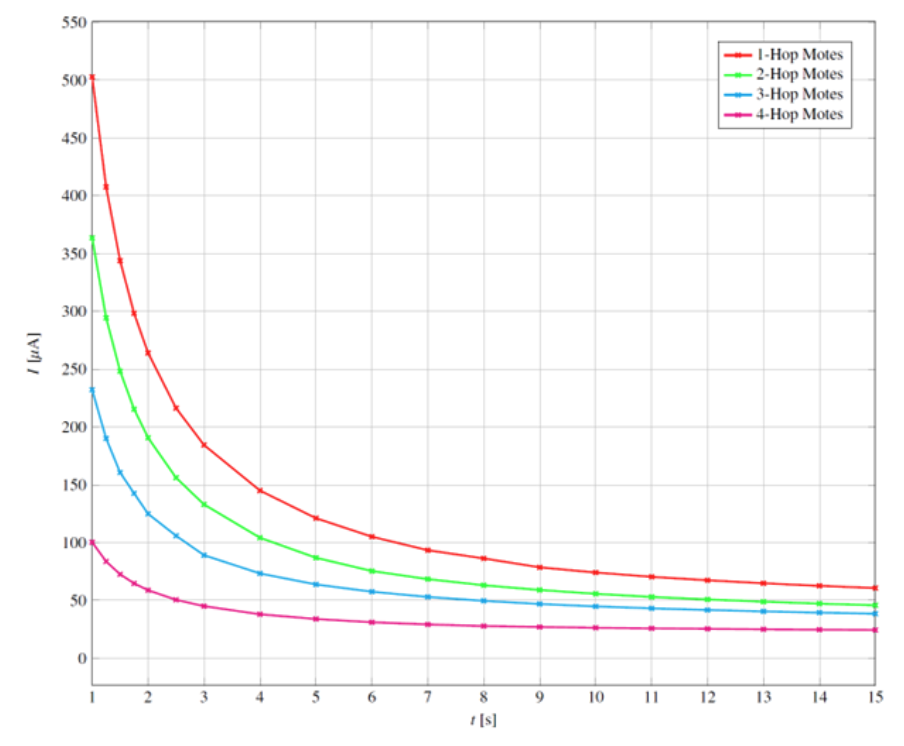

For estimating the current consumption of the motes in the network, we rely on the SmartMesh IP Power and Performance Estimator 9. The tool is publicly available and estimates the power consumption of a SmartMesh IP network based on different parameters. It also allows one to draw conclusions on the battery lifetime. To use the estimator for our HW setup we need to make some assumptions on the network. First, we assume that the power consumption of the application chip is comparatively small in contrast to the radio activity at the networking chip. Furthermore, a constant neighbor link PDR/path stability of 80% is presumed. The resulting simulation to estimate the average current draw of each mote is done based on a network consisting of 20 motes in total and a maximum hop-depth of 4. We assume that the motes are split up equally along the hops, i.e., 5 motes on each hop-depth. Further simulation parameters are a temperature of 25° C and a constant payload size of 80 B.

The average current draw is calculated in the simulation based on varying heartbeat intervals. The aim is not to show the overhead of the monitoring solution on the actual system performance but to demonstrate the impact of increasing reporting interval lengths on power consumption. Thus, we simply assume that the transmission rate of the actual application rises proportionally with the heartbeat rate and that the application payload is already part of the simulated payload.

We observe that the motes consume less when having a larger hop-depth. Obviously, these hops have fewer children than for instance, the 1-hop motes, which need to forward the traffic from the deeper motes in the mesh, and therefore power consumption will go up with increased radio activity. Furthermore, the simulation shows a high slope in current draw for the 1-hop, 2-hop, and 3-hop motes when shortening the heartbeat interval lengths. In contrast to that, saturation is visible for almost all hop-depths when the interval is greater than 10s. There is a minimum report rate below which the impact on power consumption is negligible. The reason is that in a SmartMesh IP network, there is some quantity of radio traffic needed to maintain time synchronization across the network. The simulation clearly shows the costs in power consumption related to an increasing heartbeat interval duration.

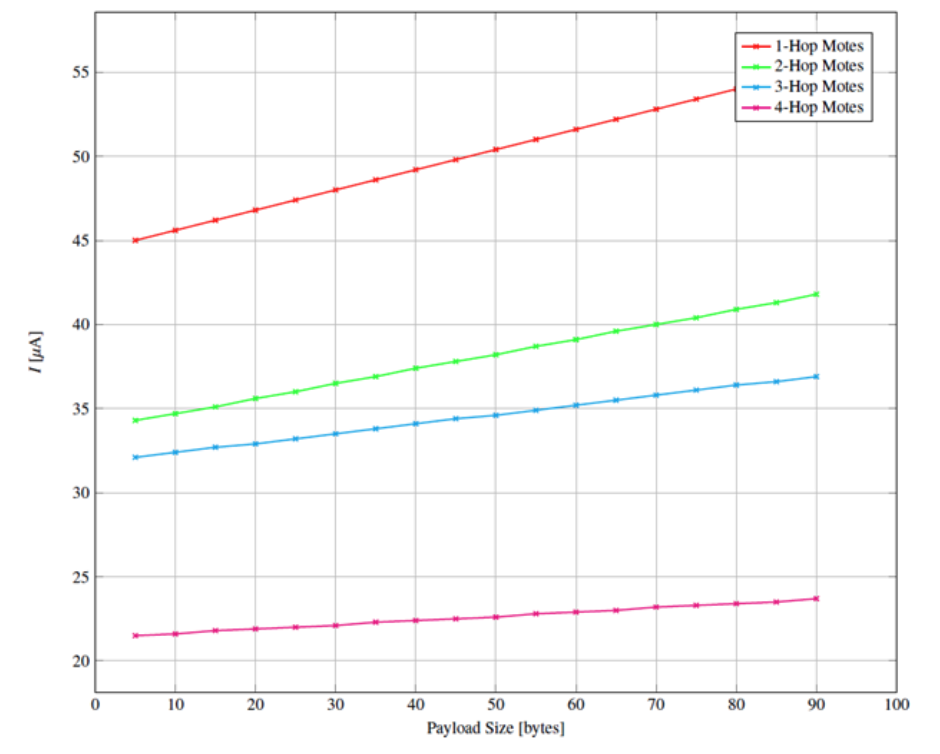

The current draw of motes in wireless systems based on IEEE 802.15.4 is indeed dominated by the number of packets and not so much by the packet size. This means it is more efficient to put more payload in one packet instead of splitting it up on two packets. Nevertheless, power consumption is still increasing with growing packet size. We now fix the heartbeat reporting interval length to 20s and vary the transmitted payload size.

Obviously, the energy saved by choosing smaller heartbeat interval lengths is an order of magnitude higher than the saving by smaller payload sizes achieved through data aggregation and data compression. Nevertheless, especially in ultra-low-power wireless systems, every possibility of saving energy must be exploited to extend the battery lifetime of the motes.

Conclusion

Future work will involve developing and analyzing methods for data aggregation and data compression in the context of APM. We conclude this post by discussing the benefits of the presented APM framework in contrast to the introduced overhead in terms of power consumption. We have highlighted that choosing a reasonable heartbeat interval length, i.e., not smaller than 10s, and an efficient way of compressing the payload containing the metrics and the corresponding meta-information, is the key to tipping the balance in favor of the benefits. Since Memfault is highly scalable thanks to an efficient strategy avoiding sending the metric identifiers in each packet and by using CBOR, it seems well suited for monitoring these kinds of networks.

See anything you'd like to change? Submit a pull request or open an issue on our GitHub

References

-

Monitoring Performance Metrics in Low-Power Wireless Systems. Fabian Graf, Thomas Watteyne, Michael Villnow. Elsevier ICT Express Journal, Volume 10, Issue 5, Page 989-1018, 2024 ↩

-

Xavier Vilajosana, Thomas Watteyne, Tengfei Chang, Mališa Vučinić, Simon Duquennoy, et al.. IETF 6TiSCH: A Tutorial. Communications Surveys and Tutorials, IEEE Communications Society ↩

-

T. Watteyne, L. Doherty, J. Simon and K. Pister, “Technical Overview of SmartMesh IP,” 2013 Seventh International Conference on Innovative Mobile and Internet Services in Ubiquitous Computing, Taichung, Taiwan, 2013, pp.547-551. ↩

-

X. Vilajosana, T. Watteyne, M. Vučinić, T. Chang and K. S. J. Pister, “6TiSCH: Industrial Performance for IPv6 Internet-of-Things Networks,” in Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 107, no. 6, pp. 1153-1165, June 2019 ↩

-

https://www.analog.com/media/en/simulation-models/software-and-simulation/SmartMesh_Power_and_Performance_Estimator.xls ↩