A Simple Scheduler via an Interrupt-driven Actor Model

Using an RTOS is often a tradeoff between the ease of decomposing tasks, with the complexity of the scheduler itself. There exists a middle ground between highly complex systems that may require an RTOS, and simpler ones that can be easily modeled using a super loop.Since ARM is the most popular embedded CPU and almost every ARM processor has a hardware scheduler, it would be interesting to make a compact framework utilizing these features. The most popular approach to RTOS-less event-driven systems is super-loop consuming events produced by interrupts. This article discusses an alternative, more efficient approach in some circumstances. It has less overhead than an RTOS and also benefits event-driven systems.

One of the main benefits of an RTOS is task decomposition to independent concurrent threads with configurable priority. Typically, it enhances the system’s maintainability, reduces complexity, and facilitates subsequent development. But this is not free. The RTOS kernel takes up a portion of system resources and introduces new issues because of its complexity. Also, bugs related to concurrency and synchronization are known to be the hardest things to fix. Loop-based solutions are cumbersome and have a bad reputation because they don’t respond quickly.

This is why concepts where interrupts are used as the main ‘execution engine’ are so popular. Interrupts have low overhead, but they allow for preemptive design. In their latest MCU designs, ARM even made handlers that can be written in C. But, writing application logic in interrupt handlers makes it hard to break tasks down, as it might be in the RTOS case. Our goal is to describe an alternative approach that reuses the hardware properties of the interrupt controller to allow both task decomposition and overall framework simplicity.

In this article, we’ll weigh the benefits of using the Cortex-M interrupt model as a scheduler and go over a simple implementation of this concept.

Table of Contents

The Hardware Scheduler

Before we dive into our interrupt scheduler, let’s look at how the typical preemptive RTOS scheduler works. First, it keeps a set of threads with some user-defined priority. Second, threads may activate each other, either directly or indirectly. Third, the scheduler is responsible for ensuring that the most prioritized thread will be active and activation of other threads will trigger ‘rescheduling’ and possibly preemption of the currently active one.

If you look at the programmer’s model of interrupt controllers like NVIC or GIC, you will notice that these devices do exactly that. For example, in the NVIC case, the device contains a set of registers describing the state of interrupt vectors, their priorities, and so on. Also, it has a special register called STIR (Software Trigger Interrupt Register). Writing a vector number to that register causes the corresponding interrupt to be activated in the same way as hardware does. Since the user can also change the priority of interrupts, the interrupt controller itself may be treated as a simple scheduler or an implementation of the so-called actor model in a hardware peripheral.

The Concept

The classic actor model describes an actor as a message handler, similar to an interrupt handler. When handling messages, the actor may:

- create new actors

- send messages to other actors

- read/write its local state

Actors use messages and queues to communicate. Since the interrupt controller has no such functionality, it should be implemented in software. So, there are only three types of software objects: queues, actors, and messages.

Despite the actor and its mailbox being tightly coupled in classic models, it is less practical than relying on separate queues. The latter case is more flexible. Depending on the message being processed, an actor may choose which queue to poll. Here, it is assumed that the actor may only have one message, and it has to poll some queue every time it finishes handling the current message.

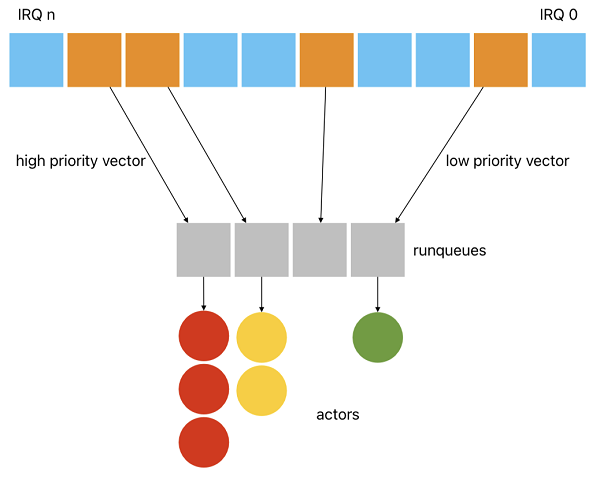

All available interrupt vectors are divided into two classes: those producing and consuming messages. Interrupts designated to peripheral devices are expected to post messages to queues that, in turn, have subscribed actors.

Let’s implement the simplest ‘blinky’ application with one actor who handles messages from systick interrupt and controls onboard LED. The whole source of the example for the STM32 Bluepill board may be found here. The messages must be sent from systick interrupt to the actor controlling the LED. Therefore, the message payload is the next LED state:

struct example_msg_t {

struct message_t header; /* Any message must have the header */

unsigned int led_state; /* Payload */

};

The systick interrupt handler may be written as follows:

void SysTick_Handler(void) {

static unsigned int led_state = 0;

led_state ^= 1;

struct example_msg_t* const msg = message_alloc(&g_pool); /* Allocate new message */

if (msg) {

msg->led_state = led_state; /* Set message payload */

queue_push(&g_queue, &msg->header); /* Send to the queue */

}

}

Interrupt handlers that are dedicated to actors contain only a call to the function, examining a list of active actors with priority corresponding to that vector:

void USB_LP_CAN1_RX0_IRQHandler(void) { /* Unused vector that is reused for actor execution */

context_schedule(EXAMPLE_VECTOR);

}

At startup, each actor subscribes to a queue. Once the message arrives in that queue, the actor is activated. Actor activation means it gets a pointer to the message, and its state is changed to ‘ready’ so the scheduler can choose it on the next scheduling call. As each actor is permitted to subscribe to only one queue, the subscription may be implemented as a return value, wherein the actor must provide a valid pointer to the queue to which it wishes to subscribe. The values an actor returns may change over time but must always be a valid queue.

static struct queue_t* actor(struct actor_t* self, struct message_t* m) {

const struct example_msg_t* const msg = (struct example_msg_t*) m;

if (msg->led_state == 0) /* Set LED according to message payload */

GPIOC->BSRR = GPIO_BSRR_BR13; /* LED off */

else

GPIOC->BSRR = GPIO_BSRR_BS13; /* LED on */

message_free(m); /* Return the message to the pool */

return &g_queue;

}

Queues can have both messages and actors. If someone writes a message in an empty queue, it will stay there until someone asks for it. If an actor tries to get a message from an empty queue it will be saved as a subscriber, and later, when a message comes in, it goes into the actor’s mailbox. It is, therefore, possible for a queue to contain either messages or actors but never both. Notably, the queue is merely a head of a linked list, lacking internal buffers, thereby preventing any possibility of queue overflow.

For simplicity, messages are fixed-sized. A message allocator is just a pool of fixed-sized memory chunks. When a message pointer gets to an actor, it is assumed that the message type is known to the actor because it knows what queue it polls. The system is also inherently asynchronous and even applicable to multiprocessor systems since (in the case of GIC) you may also trigger interrupts on other CPUs.

How it Works

Let’s look at the concept above in more detail. MCUs have a lot of interrupt vectors, but only a few are used in each application. Usually, unused interrupt vectors are disabled and mapped to panics or infinite loops. This approach aims to reuse vectors unused by devices in that given application and map actor priorities to these vectors. In other words, actors with priority N are associated with interrupt vector X, which is adjusted to have priority N. Therefore, when actors activate each other (indirectly, via message passing using queues), they trigger interrupt vectors associated with the target actor’s priority. All the work related to preemption, delaying, etc., is done in hardware, and we shouldn’t even be concerned about it (this also means that we don’t have to write any code). It is up to the user which exact interrupt vector is mapped to each runqueue. Users are responsible for setting appropriate priorities for vectors to reflect their actual preemption priority (for example, runqueue 0 has the lowest priority, so the vector corresponding to runqueue 0 should have the lowest priority among all the other vectors). Simplified pseudocode for push may be written as:

push(queue, msg) {

if no waiting actors

enqueue msg

else

dequeue waiting actor from queue

save msg pointer into actor object

request interrupt associated with the actor

}

If an actor has been activated, it causes the corresponding interrupt vector to be triggered. As with a thread scheduler, a global context contains runqueues, or ready-to-run lists. Each such runqueue is assigned an interrupt vector. So, the schedule function may be implemented as follows:

context_schedule(this_vector) {

until runqueue associated with this_vector is nonempty

dequeue next actor

call actor's function with saved message

}

As actors and interrupts, which are utilized by devices and produce messages, constitute the sole executable entities in this design, it implies that no threads are present in this system. Since there are no threads, main() is just an initialization. The second important point is that actors are run-to-completion routines. It means they only need a stack frame when running, so actors can use a common stack.

When a hardware interrupt occurs, it allocates and posts a message to a queue. This causes the subscribed actor to be activated, the message to be moved into its incoming mailbox, the actor to be moved to the list of ready ones, and the interrupt vector corresponding to the actor’s priority to be triggered. After the interrupt handler is finished, the CPU hardware automatically transfers control to the activated vector. Its handler then calls a function called ‘schedule,’ which eventually calls the corresponding actor.

During this process, the system remains fully preemptable and asynchronous: other interrupt handlers may post messages to other queues. If the actors are delayed, then messages will be accumulated in queues. When an actor or interrupt triggers another high-priority actor, preemption is initiated immediately.

It is important to emphasize that the interrupt vector is assigned to a priority level, not an actor, so the total number of actors is unlimited:

It’s clear that the number of possible priorities is limited to the number of interrupt vectors and available hardware preemption priorities. Cortex-M microcontrollers can have up to 240 interrupt vectors, but only a few are used in each application. Therefore, there should be no vector shortage. If that’s the case, your application may be so complicated that a full-featured RTOS would be a better choice.

The aforementioned concept can be implemented in approximately 200 lines of C code. In the case of software implementation, the framework would have to deal with interrupt frames, their patching to emulate preemption, calls for rescheduling on interrupt return, examining bitmaps to find the most prioritized runqueue, etc. With hardware-assisted implementation, you can get all of this functionality for free.

Pros & Cons

Interrupts are often used as a simple ‘execution engine’ in RTOS-less embedded systems. While it is better than loop-based solutions because of preemption, it may lead to worse latencies when complex processing is done in handlers directly. Many devices use interrupts for various reasons; for example, communication devices use them to signal transmission completion, new data receiving, errors, and so on. When the data is processed in handlers, it may block responses to other events, which may be undesirable, especially when communication protocol has timing constraints, like USB, where the host pings devices periodically. It’s a good idea to split interrupt handlers into several parts and keep interrupt code as short as possible to be able to respond to other incoming events. This approach may be a way to achieve such a split. Also, actors may be put in another environment, like a host computer, for testing purposes.

Furthermore, it may also help with processing events from multiple sources and utilizing multiple CPUs. For example, interrupt controllers for multi-core chips (i.e. ARM GIC, see GICD_SGIR) can trigger interrupts on other cores too (while also enforcing priorities and all the other things described above). Thus, the target CPU core may easily augment an actor’s associated vector. In this design, each core has its own run queues, just like threads do. Posting messages to a queue may activate subscribed actors running on different cores, enabling true parallel message processing. While ‘big’ multi-core chips usually run Linux, they are not the ideal target hardware for such a simple framework, but this case is possible. It’s worth considering when ultra-low latency is crucial, and every tick counts.

The most significant disadvantage of the model is its requirement to redefine the task in terms of actors and messages (publish-subscribe model), which may be difficult. Consider implementing timeouts or waiting for a response before further message processing. Since the actor model relies on message allocations, it is less deterministic than fixed-memory solutions, like threads and semaphores. When message pools are exhausted, it is still being determined how the handler should proceed. In other words, design patterns for the actor model are less known and may be more complex than their threading-based counterparts. Nevertheless, this may be fixed sometimes by utilizing ‘async/await’ features of modern languages like Rust and C++20. With async functions, the actor’s code may be expressed more naturally and sequentially without manually creating state machines.

Final Thoughts

The actor model has been around since 1973. It can help with modularity, testability, power efficiency, and configurability in embedded systems. Using hardware-implemented scheduling allows for further simplified source code while also speeding up scheduling operations. Suppose your application uses a few interrupt vectors, and your implementation of an interrupt controller allows you to use others. Reusing these vectors for your needs may be a good decision. However, remember that this is largely dependent on the implementation. For example, the NVIC spec is fixed, but the count of available priorities and vectors may vary from one vendor to another. So, while not all systems are suitable for the actor model, it may be a good choice for some, and hardware implementation of model parts in widely available MCUs makes it even more attractive.

See anything you'd like to change? Submit a pull request or open an issue on our GitHub

Further Reading

- The actor model in 10 minutes: https://www.brianstorti.com/the-actor-model

- Actor Model Explained: https://finematics.com/actor-model-explained

- NVIC operation: https://developer.arm.com/documentation/ddi0403/d/System-Level-Architecture/System-Address-Map/Nested-Vectored-Interrupt-Controller--NVIC/NVIC-operation

- Using Preemption in Event Driven Systems with a Single Stack: https://www-docs.b-tu.de/fg-betriebssysteme/public/publication/2008/walther-usingpreemption.pdf

- Embassy async framework https://embassy.dev