Comparing Firmware Development Environments — Linux, Windows, WSL2, and VMWare

About a year and a half ago, I decided to take a different approach to setting up a Zephyr environment for a new project at Intercreate. Instead of using my trusty VMWare Workstation Linux VM, I opted for WSL2. I was curious to find out: Would hardware pass-through for debugging work reliably? Would all of the tooling dependencies be supported? What about build system performance?

Not only did everything go smoothly, but since then, many colleagues have also moved from native Linux or traditional VMs to WSL2 and seen great results.

In this article, I’ll guide you through the trade-offs that come with the use of various development environments, comparing four common development environments:

- Ubuntu 24.04 (Kernel 6.8)

- Windows 11

- VMWare Workstation Pro 17

- WSL2 2.2.4.0 (Kernel 5.15)

I’ll evaluate each setup’s strengths and weaknesses to help you choose the best option for your firmware development needs. This is by no means exhaustive, and I’d welcome further feedback in the comments! Some Zephyr benchmarks were devised in order to quantify performance of common Zephyr toolchains.

Table of Contents

Features and Limitations

The table below lists some of the common features that are assessed for a firmware development host environment. Yes, you do need graphics to view that schematic; and no, there’s not an emacs package for that.E You’ll see that a few caveats are listed for each of the virtualized hosts.

E Hold on…

| Ubuntu 24.04 (Kernel 6.8) | Windows 11 | VMWare Workstation Pro 17 | WSL2 2.2.4.0 (Kernel 5.15) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphics | ✅ | ✅ | ✅1 | ✅ |

| Network | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| USB | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| BLE | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅2 |

| Performance3 | 100% | ~50% | ~40% -> ~88%4 | ~88% |

| Developer Experience5 | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐ | ⭐⭐⭐⭐ |

1 VMWare Workstation Pro, when run headless, has the typical “X forwarding” setup curve. You can choose to emulate the graphics instead of forwarding if you are OK with the overhead and latency.

2 Not supported by default, discussed below.

3 % of bare metal Ubuntu 24.04 performance, based on a Zephyr benchmark, discussed below.

4 VMWare Workstation Pro 17 tested very poorly, but I suspect that it is because I was unable to get it to use AMD-V. Of course, AMD-V not working while WSL2 is enabled is another negative for VMWare here! Nevertheless, I suspect that it would be similar to WSL2 performance if AMD-V / Intel VT-x are working, so I gave it “up to ~88%”.

5 The author’s personal opinion, discussed below.

Graphics

If you’ve previously set up X forwarding in WSL2, you’ll be happy to learn that this is no longer necessary. Linux GUIs “Just Work” in WSL2!

Network

It’s no surprise that WSL2 can do anything you need over the network, since one of its primary use cases is web development. For example, you can establish remote network connections, SSH in and out, and host web servers—including containers—that will be available to the Windows host—or even the LAN!

USB

usbipd-win is officially recommended by Microsoft and provides a stable foundation for USB forwarding including automatic attach by both port and device.

BLE

Even laptop BLE chips use USB, so you can easily forward an integrated or

dongled BLE device to WSL2. However, the default WSL2 kernel does not include

CONFIG_BT=y and other modules that may be required for your specific chip. You

will need to compile your own WSL2 kernel (it only takes about 10 minutes!) and

see the discussion over

at usbipd-win. Please

let Microsoft know that this

feature would be appreciated!

Performance

A lot of the confusion about WSL2 performance is caused by experiences with

earlier versions of WSL or use of the Windows file system. Regarding the file

system, it’s important to understand that WSL2 creates a complete Linux file

system, from / up. You want to do your work there, probably under

/home/<user/, just like you would on Linux—because you are on Linux! While

it’s nice that you can use bash (or zsh, or whatever) and Linux apps from

anywhere on your Windows file system, there is a performance cost for doing so.

The performance differences between WSL2 and bare metal Linux are small, will continue shrinking , and are not likely to meaningfully impact your workflow.

Zephyr Benchmark

Recently, Intercreate upgraded my work laptop to the best I could find: a Framework 16. This laptop put me in a uniquely convenient position to run a benchmark due to how easy it is to run both Windows and Linux. Personally, I don’t enjoy partitioning disks for dual booting. While I appreciate improvements to security like TPM, UEFI, Secure Boot, and Full Disk Encryption, they make the dual booting process nerve-wracking enough that I am no longer willing do it on a machine that I depend on at work.

Not only does the Framework have two (relatively accessible) M.2 drive slots, it can be configured with SSD expansion cards that can boot an OS. This means that several of these cards with different operating systems can be plugged into the laptop without the performance issues associated with something like a Live USB, and without the headaches caused by disk partitioning and GRUB.

So, I set out to quantify the performance trade-offs between developing Zephyr on Native Ubuntu 24.04, WSL2 (Ubuntu 24.04), and Native Windows 11.

The Test Fixture

Hardware:

- Framework 16

- CPU: AMD Ryzen 7 7840HS

- Geekbench 6: 11,134

- similar to an Intel Ultra 9 185H (12,110) or Apple M3 @ 4.1GHz 8 CPU/10 GPU (11,704)

- Geekbench 6: 11,134

- RAM: 32GB 5600 MHz DDR5 (2x CT16G56C46S5.M8G)

- Windows (and WSL2) Storage: 2TB NVME (CT2000T500SSD8)

- Ubuntu Storage: 250GB USB 3.2 Gen 2 (FRACCFBZ02-2)

- CPU: AMD Ryzen 7 7840HS

- MacBook Pro (16-inch, 2023)

- CPU: Apple M2 Pro @ 3.49GHz 12 CPU/19 GPU (14,195)

In order to compare macOS Zephyr performance to x86 platforms that cannot run macOS, the macOS results are scaled by the Geekbench 6 difference: 14,195 / 11,134 = 1.245. For example, if a task on the Ryzen 7840HS and the M2 Pro took the exact same amount of time, 100.0 seconds, the M2 Pro result would be scaled to 124.5 seconds to account for the hardware performance difference.

Zephyr Toolchain

- Zephyr @ 40810983ead23c954bce113cb7ace50592451da4 (3.7.0-rc2)

- Zephyr SDK 0.16.8

- cmake 3.28.3

- Python 3.12.4

- ninja 1.11.1

Benchmark

A benchmark shouldn’t take too long, yet it should be long enough that it smooths over some run-to-run issues you might see—what are Windows Defender and Windows Update up to during the run 🔍?

In the Zephyr ecosystem, a tool called Twister is used to collect and run build-only, emulated, and on-target tests for Zephyr boards and applications.

A build-only twister run representing four common platforms from

ST, Nordic,

Espressif, and NXP, was

chosen in the hope that it overlaps with many developers’ everyday Zephyr

workflows. The drivers test folder was chosen because most projects would use

some drivers and the build times weren’t too long.

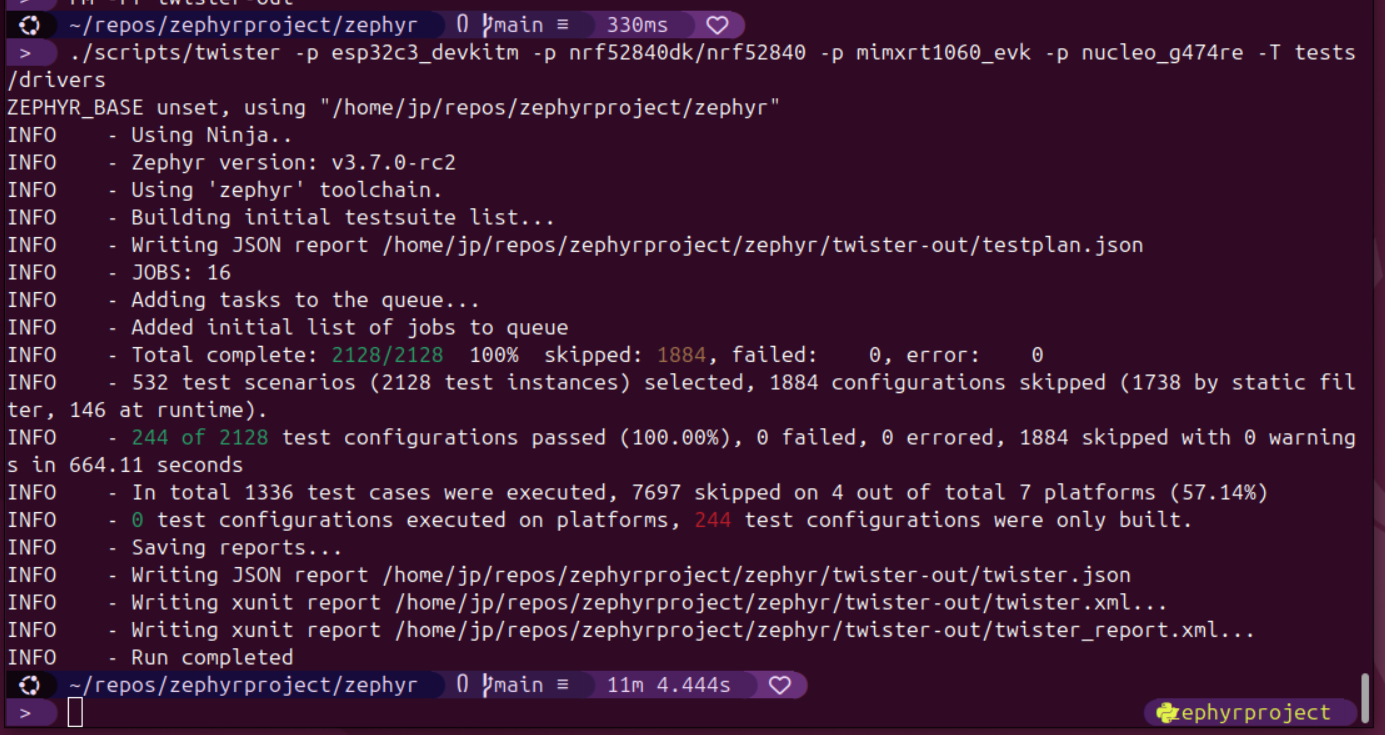

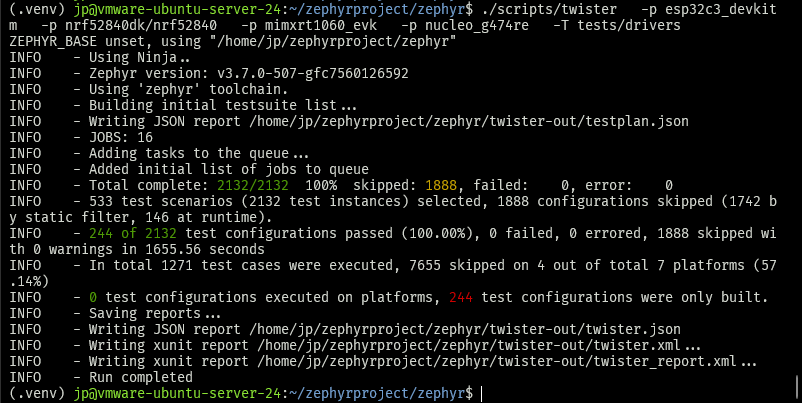

./scripts/twister \

-p esp32c3_devkitm \

-p nrf52840dk/nrf52840 \

-p mimxrt1060_evk \

-p nucleo_g474re \

-T tests/drivers

This command selects a total of 244 test builds between the four platforms. Some boards, like nrf52840dk, have more driver tests than the other boards.

244 Builds

- 55 nucleo_g474re (ST)

- 108 nrf52840dk (Nordic)

- 32 esp32c3_devkitm (Espressif)

- 49 mimxrt1060_evk (NXP)

Problems

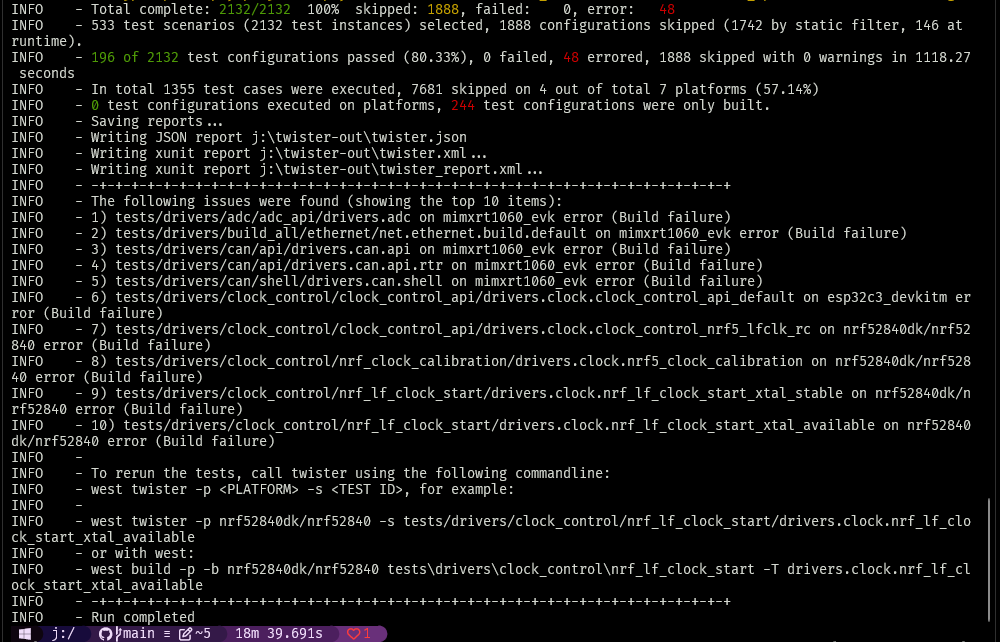

- A new reason not to use Windows as your development environment! While path length limitations have been mitigated by Microsoft, toolchains have not caught up. I gave up trying to fix it and I’m not sure whether it’s a CMake or Ninja problem. Even after I used a workaround where I shortened the paths by assigning the root build path to a driver letter, still 48 of the 244 tests errored due to some object in the build exceeding the max path length. This is an open issue at Zephyr.

- The native Ubuntu run is on a different disk than the Windows and WSL2 tests. While the Windows NVME drive is faster than the USB 3.2 Gen 2 drive, the test is expected to be primarily CPU bound instead of being bound by the 1,000MB/s read and 800MB/s write speeds of the SSD expansion card.

- Operating systems. They do stuff. It’s hard to know why and when they do that stuff! All tests were run with a single Chrome instance open on a default tab and the system set to “maximum performance”. Time permitting, the benchmark would be run many times.

- Test selection could be refined to cover a wider variety of build scenarios, targets, and toolchains.

- Couldn’t get VMWare to use AMD-V.

Native Ubuntu 24.04

Operating System: Ubuntu 24.04 LTS

Kernel: Linux 6.8.0-36-generic

Architecture: x86-64

All other platforms are compared to the Ubuntu results because Ubuntu is the fastest. For every platform, the duration of a Ubuntu 40 second long build is compared. 40s was chosen as the nominal build time because it’s a relatively long build that I observed for a Zephyr project that used lots of libraries like LVGL, nanopb, crypto, and BLE and many peripheral drivers like ADC, SPI, USB, and I2C. This project’s executable could be as big as 900kB.

| Metric | Result | Compared to Native Ubuntu |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | 11m 4.444s | - |

| Average build duration | 2.723s | - |

| Workload multiplier | 1.000 | - |

| Duration of a 40s build | 40.000s | - |

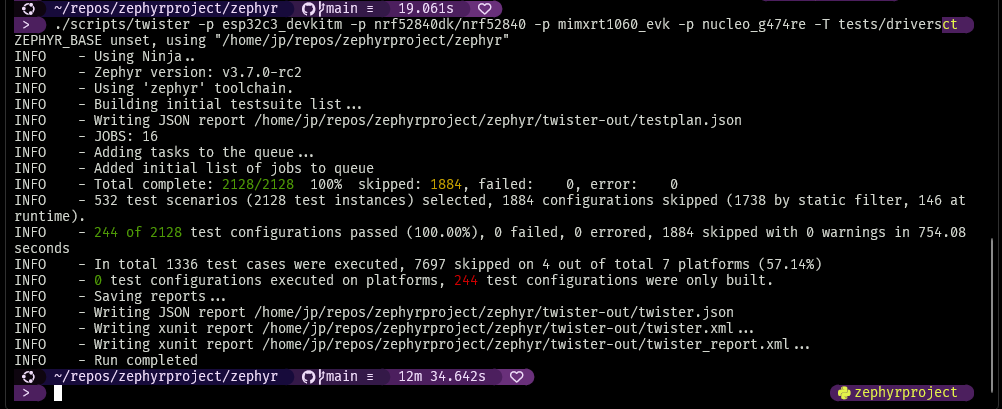

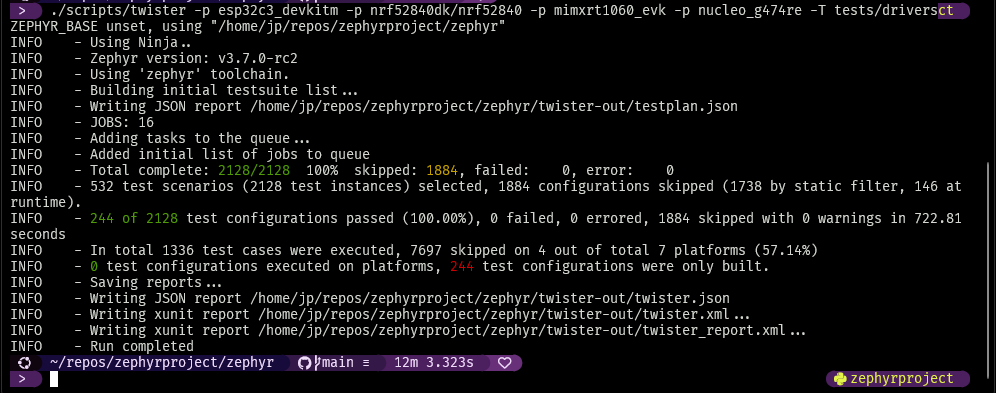

WSL2 Ubuntu 24.04

Virtualization: wsl

Operating System: Ubuntu 24.04 LTS

Kernel: Linux 5.15.153.1-microsoft-standard-WSL2

Architecture: x86-64

| Metric | Result | Compared to Native Ubuntu |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | 12m 34.642s | + 1m 30.642s |

| Average build duration | 3.092s | + 0.369s |

| Workload multiplier | 754.642s / 664.444s | * 1.136 |

| Duration of a 40s build | 40.000s * 1.136 = 45.440s | + 5.440s |

I also compiled Kernel 6.1 and 6.6 for WSL2 and saw that Kernel 6.1 shrank the performance gap by about 4%. In my opinion, that’s not worth it, but it shows that WSL2’s upcoming upgrade to Kernel 6.6 may come with some more performance gains.

Virtualization: wsl

Operating System: Ubuntu 24.04 LTS

Kernel: Linux 6.1.21.2-microsoft-standard-WSL2+

Architecture: x86-64

Windows 11

Tip: One of the main things that slows down build systems in Windows is Windows Defender. Build systems do a ton of file IO and Windows Defender scans go wild during the build. For this test, I disabled Windows Defender entirely, which you should never do. Instead, you should painstakingly ignore your build folders and toolchains in Defender settings and pray for better support from Microsoft someday!

Note: Windows 11 wasn’t able to properly complete the benchmark due to issues with long paths generated by the build system. I’ve compiled Zephyr projects on Windows many times without (too many) problems, but this issue does give me pause. Well, that, and it being half the speed of WSL2, at best!

| Metric | Result | Compared to Native Ubuntu |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | 23m 13.901s (includes a 274.201s penalty for errored tests) | + 12m 9.457s |

| Average build duration | 5.713s | + 2.990s |

| Workload multiplier | 1,393.901 / 664.444 | * 2.098 |

| Duration of a 40s build | 40.000 * 2.098 = 83.920s | + 43.920s |

VMWare Workstation Pro 17 (no AMD-V)

Virtualization: vmware

Operating System: Ubuntu 24.04 LTS

Kernel: Linux 6.8.0-39-generic

Architecture: x86-64

| Metric | Result | Compared to Native Ubuntu |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | 27m 35.400s | + 16m 30.956s |

| Average build duration | 6.785s | + 4.062s |

| Workload multiplier | 1,655.56 / 664.444 | * 2.492 |

| Duration of a 40s build | 40.000 * 2.492 = 99.680s | + 59.680s |

Ouch. Because I was unable to get VMWare to use AMD-V, this benchmark went extremely poorly for VMWare. Performance on par with WSL2 should be expected when VMWare is configured correctly for AMD-V or Intel VT-x, but let this benchmark be a reminder that you shouldn’t take configuration and compatibility for granted!

Results Compared

The Zephyr Benchmark duration in seconds of all of the tests described above are graphed below.

* macOS Sonoma had the fastest result of 595.620s, but the value in the chart, 741.547s, is scaled in an attempt to account for CPU performance differences between the x86 and Arm test platforms.

Developer Experience

This is a subjective 5-star rating of my personal Firmware Developer Experience™ with the platforms discussed in this article. I’d love to hear about other people’s experiences!

Linux

⭐⭐⭐⭐

Pros:

- Control: You have choice of distro, desktop environment, kernel, and more.

- Zephyr performance is the fastest of the platforms I tested.

- It’s free!

- 🐧 Cute penguin mascot!

Cons:

- Security:

- Full disk encryption is not a default in major desktop distros like Ubuntu and Fedora, leaving it up to IT departments or employees to enable and support.

- Many companies and developers distribute software and scripts that are unsigned, leaving users open to attacks that impersonate their tools. Install scripts may require sudo and users that have become used to running scripts like this may be unaware that they are willfully disabling Linux’s security model. Heck, I’ve even seen inline binary in unsigned bash scripts—a hacker’s dream!

- Hardware Support: Linux desktops tend to be much slower to receive driver support from manufacturers, if they receive driver support at all. Sometimes you have to wait for a community developed solution.

- Software Support: Many tools in the Hardware and Electrical Engineering fields do not have Linux support.

- Your users probably don’t use Linux desktop. So when you’re developing tooling for them, you’ll probably want to test on macOS or Windows.

In a bubble, booting Linux provides the perfect experience for development. However, considering the wider ecosystems, I chose to dock one star for the baggage that comes with Linux desktop: no agreed upon FDE, hardware and software compatibility issues, security hubris, and minimal market share.

WSL2

⭐⭐⭐⭐

Pros:

- You get most of the pros of a Linux environment and all of the pros of the Windows host.

- Resource allocation is automatic. You can fiddle with CPU and RAM allocation, but you shouldn’t need to. Storage is automatically resized as needed, so you never need to worry about running out of space for your WSL2 environment.

- Setup is very simple — you can follow Intercreate’s tutorial below — and supported by Microsoft.

Cons:

- Minimal choice of distros and fewer options for customizing your installation and kernel. That’s not to say that you can’t, but rather that you will stray outside of the Microsoft support umbrella by doing so.

- BLE, and probably other kernel modules that I haven’t thought of, are not enabled in the default WSL2 configuration.

- Performance is not as good as running Linux on bare metal.

Windows 11

⭐⭐

Oh, Windows. WTF. Microsoft has made a lot of progress towards making software development a first-class experience, but there’s still a lingering je ne sais quoi when using Windows.

Well, now we know one thing: it runs Zephyr builds at half the speed of Linux!

Pros:

- Security:

- Full disk encryption (BitLocker) is default and your recovery key is backed up to your Microsoft account.

- Unsigned applications and scripts produce a warning. (This is also a con.)

- Hardware Support: If your product doesn’t support Windows on release, then it’s dead on arrival.

- Software Support: mechanical and electrical engineering tools have long been built for Windows.

- Your users probably use it, so you’ll need to support it anyway.

Cons:

-

Zephyr performance is half the speed of Linux.

-

Security:

- Developer mode removes warnings about unsigned scripts and applications.

- Microsoft requires yearly payment — previously, to an approved certificate authority, now you have the option of paying MS directly — in order to sign scripts and applications. This has resulted in the widespread use of unsigned scripts and applications. Even huge projects like Rye and WezTerm will trigger false positives for Trojans in Windows Defender and require the user to click through “scary warnings.” The global software ecosystem lives and dies by OSS and creating barriers to signing and authentication of OSS is dangerous for Microsoft’s customers and business.

-

It’s $200, but you might never notice that when purchasing new laptops.

-

It’s Windows. This is more of a “gut feeling” thing that I can best explain with an anecdote. As I was setting up my new laptop, I used my Microsoft account when installing Windows, something that I had long avoided, not really for any specific reason. It felt like I could potentially avoid “Windows problems” by being compliant here. It went OK, except that it never prompted me for the name of my home (user) folder and then it named it incorrectly: “jphut” instead of “jp”. Now, many people would have left it there. And perhaps I should have. But “jphut” is wrong. Home is at

/home/jp, orc:/users/jp, or/users/jp- this is how it has always been. “No big deal,” I thought. “I’ll fix it!” It took me 3 hours. RegEdit. Reviewing scripts left on Windows forums. Seriously breaking my install. Adding symlinks for OneDrive. It’s been working fine for a few months now, but for all I know I’m out of spec in a weird way that will cause problems. -

📎Unsettling paperclip mascot!

VMWare Workstation Pro

⭐⭐⭐

Pros:

- With a fully featured VM, you get most of the pros of Linux with access to Windows’ strong points when you need them.

- USB forwarding, including BLE, works well because you can run a full Linux distro of your choice with all the kernel modules that you need.

- SSH to a headless VM allows for a snappy, low-latency, experience in your terminal emulator and editor of choice.

Cons:

- Setup and maintenance. VMs are complicated, and setting up and maintaining the VM takes time and research. A common example is the allocation of disk space. Generally, you will need to allocate the space for your guest OS up front. It can be hard to predict exactly how much space you really need, so you may end up needing to expand the virtual disk at some point, requiring steps to be taken from both the host and guest.

Conclusion

Ultimately, choosing the right development environment comes down to what will help you to be most productive. Decisions about security, performance, features, and stability must be weighed distinctly within each organization and project. Personally, I’ve found a nice balance by using WSL2 on Windows 11. It offers the security, stability, compatibility, and support of Windows while still allowing me to use my preferred tools in a Linux environment.

Any concerns about performance are eased by quantifying that a WSL2 Zephyr build system is only ~12% slower than bare metal Linux. For example, even if you were compiling big Zephyr projects with 40-second build times, 20 times a day (which I’m not), WSL2 would only cost you an extra 1 minute and 30 seconds of compile time. For the tools my work requires, that is a small cost to pay for all the benefits that the Windows host provides.

If you’re interested in trying out WSL2 for firmware development, check out the complete tutorial, or subscribe to the Interrupt blog to receive the follow-up to this post as soon as it’s published.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Seth Woiszwillo for running the macOS benchmark and the entire Intercreate team for their help with this article.